The Principle of No Free Riding complements that of No Double Counting (summary); both form part of Circular Guidance Note 1 (Full Note); both Principles safeguard the environmental and social integrity of the Circular Credits Mechanism and of the waste management systems of its users.

No Free Riding has fairness at its heart: The Circular Action Hub only recognises the environmental service of activities that are fairly paid for, importantly, in addition to payments for the acquisition of physical recyclable materials.

SEPARATING THE TWO CONCEPTS

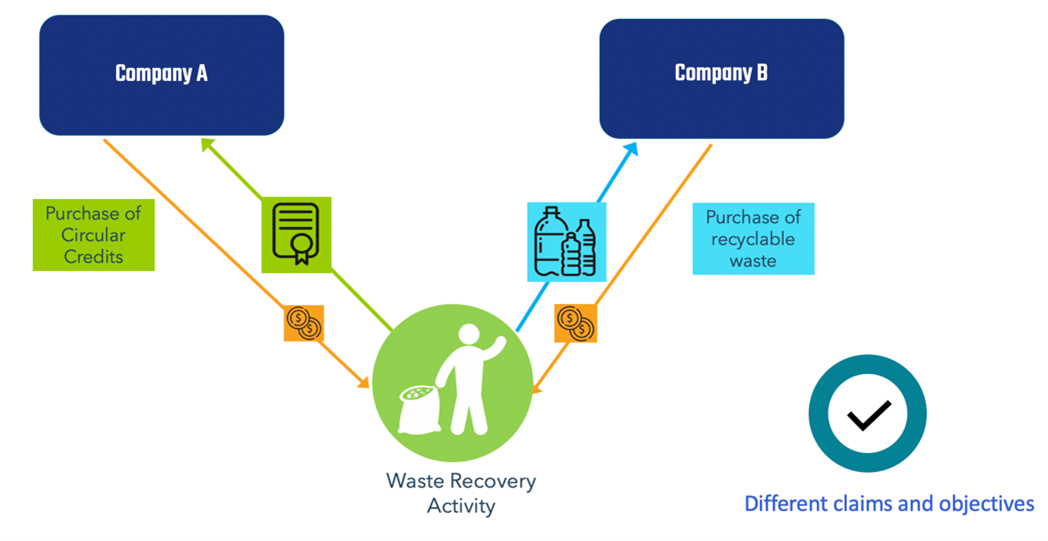

The separation of concepts (‘purchase of physical recyclable material’ and ‘payment for the activity of waste recovery’) is also vital to avoid situations of ‘free riding’. For example, if a cooperative of waste pickers can sell their physical materials to one company, and the circular credits for another one. Two products, two commercial transactions.

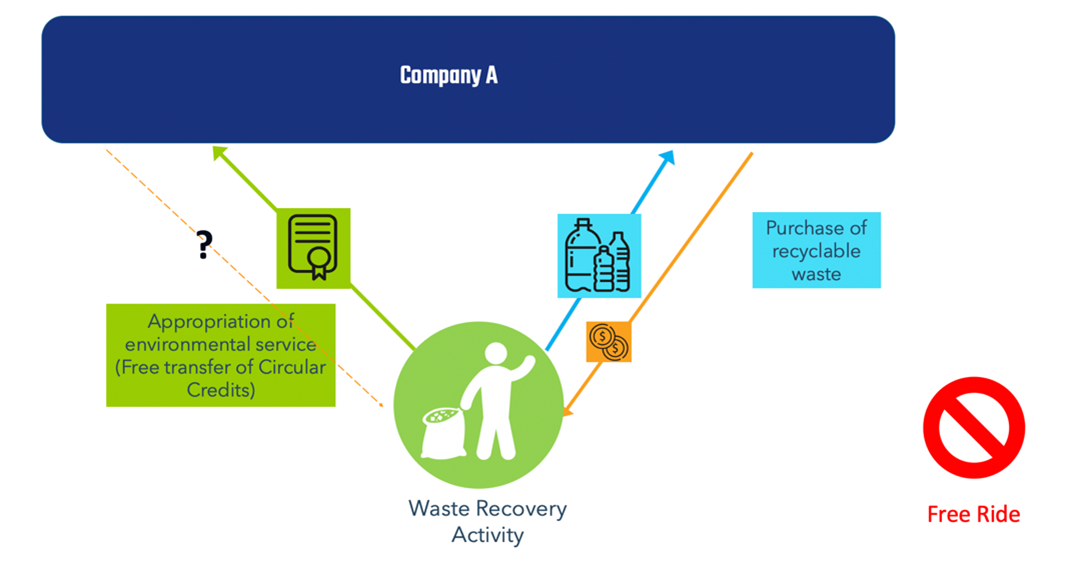

However, in some cases, a company may buy recyclable materials collected from waste pickers as feedstock to meet their targets of increased recycled content, and at the same time, also claim that the environmental service of waste recovery (i.e., credits) belongs to them, given that they acquired the material collected. We believe that, in this case, this company will be ‘free riding’ the system, avoiding to pay for the service of waste collection and sorting.

In the CCM’s view, the acquisition of physical material does not allow the company to claim they have contributed to the unremunerated activities of waste collection and recovery. If the collection and recovery of waste is not separately paid for, it would be an appropriation of the environmental service provided. In countries with EPR obligations (see below) this practice is referred to as “free riding”.

In the CCM’s view, the acquisition of physical material does not allow the company to claim they have contributed to the unremunerated activities of waste collection and recovery. If the collection and recovery of waste is not separately paid for, it would be an appropriation of the environmental service provided. In countries with EPR obligations (see below) this practice is referred to as “free riding”.

PAYMENT FOR DIFFERENT PURPOSES

Consequently, the aim of the “No Free Riding” principle is to ensure that the environmental service of waste recovery is paid for, in addition to the purchase of recyclable materials, as these payments are made for different purposes.

For instance, in cases where waste pickers are only paid for the sale of physical recyclable materials delivered to a buyer, the buying entity is not entitled to claim the environmental service provided as this is a transaction involving solely the purchase of waste materials as a feedstock for recycling plants and not a contract for the provision of an environmental service. On the other hands, buyers that want to compensate their waste footprint would be interested only on the purchase of circular credits, and not necessarily on acquiring the physical materials.

COSTS IN COUNTRIES WITH/WITHOUT EPR SCHEMES

The easiest way to understand the difference between these concepts, is to compare costs of waste management and circularity to companies operating in countries with and without EPR (Extended Producer Responsibility) obligations.

In countries with EPR obligations, companies need to pay EPR levies to ensure that the materials that they market are recovered and sent to an appropriate destination after consumption . These levies can be paid to government agencies or EPR agents that conduct the collection and recovery of such materials. If these companies decide to increase the recycling content of their products (or packaging) , they would need to incur the additional cost of acquiring recyclable material, usually sold from a different party.

In countries without EPR obligations, where the service of collection of recyclable waste materials is often incipient, vast amounts of material end up in the environment. Companies that sell or distribute products to these countries have a risk that their post-consumption products leak into nature, causing pollution and affecting their brands.

Companies may also want to buy physical recyclable materials to increase the recycled content of their products. In countries with more advanced waste management systems (which often also have EPR obligations, or equivalents), these materials are purchased from actors different from the ones that conduct waste collection in the first place.

In less specialised economies, it is often the case that the same actors conduct the collection and sorting of waste materials and also sell the recyclable fractions. The fact that the same party performs both functions should not result in them not being paid for both.

So, in essence, the acquisition of circular credits enables companies to extend their responsibility to countries without Extended Producer Responsibility regulations – by ensuring that they financially contribute to the activities of waste collection and appropriate destination.

- See, for instance, OECD 2019: Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) and the impact of online sales. Environmental Working Paper 142; or Watkins et al. 2017: EPR in the EU Plastics Strategy and the Circular Economy: A focus on plastic packaging. Institute for European Environmental Policy.

- Most EU countries have EPR obligations (see Europen reports) and these are been replicated in some developing countries (e.g., India).

- EPR levies in the Eu range from less than €100/tonne to ca € 500/tonne, depending on material and country. See, for instance Watkins et al. 2017.

- The appropriate destination for the materials collected varies according to local context. Projects should pursue the best economically-feasible destination for waste recovered available.

- In the UK, for instance, there are over 30 Producer Responsibility Organisations (PROs) – agents that assist companies in meeting their EPR obligations.

- For instance, to meet voluntary or compliance targets.